We are interested in all ocean-going power boats, but right near the top of the pack is the FPB series from Steve and Linda Dashew. We’ve seen many FPBs over the years as we completed our around-the-world run and the first things that jumps out is they are unfinished aluminum.

When we were in New Zealand we got a chance to tour Circa Marine in Whangarei where this boat and all members of the FPB series are built. We were unable to take pictures so didn’t blog the visit, but it was super interesting. FBPs are directly cut from very large aluminum plate using computer numerically controlled (CNC) cutting tables similar to those we saw at Metal Shark Aluminum Boats. These boats go from computer-aided drafting system to CNC cut panels and then to a fully-welded up boat with little grinding and re-cutting. Almost all the labor is invested in welding and the end result is precise and, if the welders are good and panels are not too thin, the result is smooth panels with little ripple without any fairing required.

We really enjoyed our visit to Circa marine to see FPBs being built but we had never actually been aboard an FPB at sea. So when Jeff Merrill of Jeff Merrill Yacht Sales, the West Coast Ambassador for FPB, called and invited us aboard, we jumped on the opportunity. It turns out it was an even better opportunity than we understood. We would have happily made the trip south from Daytona Beach to Fort Lauderdale to see the FPB 78 alone. But, in addition to that, Steve Dashew took us into the Intracoastal Waterway and out to sea for a few hours. We had great time in medium sea conditions that gave us a good chance to better understand the boat’s capabilities. Particularly interesting was Steve just leaving the boat to drift in the sea swell while we enjoyed a great lunch on an amazingly stable platform given that we were drifting in a good-size swell. Most monohulls would yield a fairly unpleasant roll if left to drift in these conditions.

Of course, a day discussing boat design with Steve Dashew is a rare treat for people like us interested in boat design and different approaches to ocean going cruisers. Steve is particularly interesting in that he combines vast personal experience at sea with a complete disdain for industry dogma. Rather than “that’s the way it’s done”, the Dashews challenge nearly every design decision made by the boating industry. With some design features, tried and well-proven designs that have been part of boat building for years is where they end up but, surprisingly frequently, they find departures from the norm that yield a super-interesting product. I think I could spend a week with Steve talking through each aspect of the Cochise design and still not be able to cover the entire boat. It was a very interesting day.

|

|

|

In the picture at the top of this post, Steve is preparing to back Cochise out into a cross-current. He only has a foot or so between the boat and the dock on one side and a fixed pilings on the other. I asked Steve how he was planning to get out without leaning heavily on these fixed hazards. His first comment was he would need to be careful to avoid damaging the dock. He was half joking, but the FPB really is a big, strong boat.

|

|

|

|

Above you can see one of the primary design characteristics of the FPB approach to ocean-going yachts. This great room design forms the center of the boat and combines a helm, a massive entertaining area and the galley. Part of the size comes from it being a 78′ boat but some of the size comes from no dividers and a near-continuous expanse of glass. The massive glass panels are a real departure from the norm in serious ocean going boats. How can this possibly be safely done? The approach is actually not that complex. If you want a vessel certified for offshore work, you need it to be strong. But “strong” comes in many materials and, although highly unusual, glass can be very strong if thick enough. Still, even if very thick, glass can fracture on impact and the fastest way to lose a boat at sea is to break a large pane of glass.

The Dashews beat this problem by taking a page from automotive saftey systems. Car front windshields are made with multiple layers of glass laminated together with a material that will flex but not fall away when the windshield is broken. The FPB approach is to use sufficiently thick glass to be offshore certifiable and then use laminated glass to keep the window intact and holding out water even if broken. It’s a creative approach to combining a great view with high margins of safety

|

|

The lower helm at the port side of the great room can be folded away when not at sea and, when at sea, this helm position is both comfortable and has a commanding view through 240 degrees. The helm includes an extensive array of Maretron display panels. Cochise is one of the few boats we’ve seen that might have more Maretron equipment on board than Dirona.

In the middle of the control cluster are thruster controls. I asked Steve what he was using for thrusters on Cochise and he said there was no stern thruster and he regretted installing the bow thruster. I said “Yeah sure, you might not need it, but others will.” He said he was told this enough times that he actually did install a bow thruster. But in sea trials, both he and everyone who tried the boat just didn’t need it. Again, I’ve heard that before but in 20 kts of wind, some of us will be thankful he installed it. He laughed and said it really was so unnecessary that he took it out of service and welded plate over the hull openings. Really? He said “I’ll show you how maneuverable it is once we are underway.” Later in the trip he drove that point home by taking the boat down a narrow, dead-end canal off the Intracoastal Waterway and turning the boat around with only feet to spare in a 20 kt cross wind.

|

|

As amazing as the visibility is from the great room, up above it in the fully-enclosed pilot house it’s truly stupendous. Love that view!

|

|

The master stateroom and master shower on the FPB 78 Cochise. Both are spacious with clean and simple design lines.

|

|

|

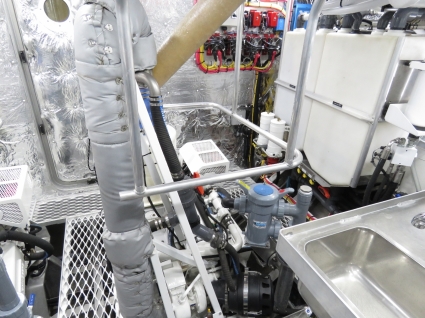

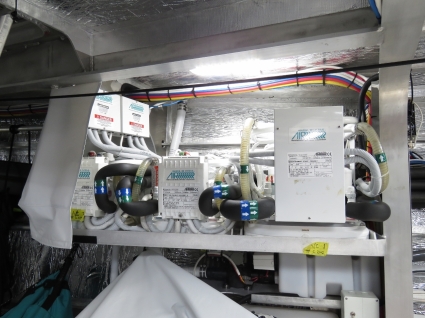

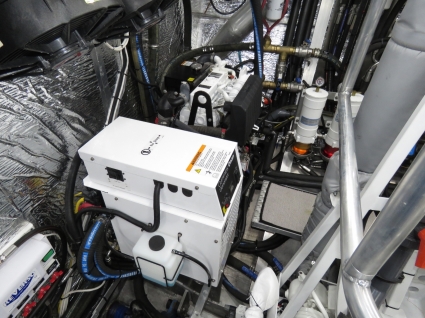

In the first picture above, Steve is showing the large Victron inverters that power Cochise. We use Victron as the 240V inverter on Dirona. The second picture above is in the engine room looking forward and slightly to port from the back of the engine room. You can see the port side main engine and a bit of the Onan Generator. The main engines are the same as the single John Deere 6068AFM75 that has reliably propelled Dirona for 8,600 hours. It’s a durable and fuel efficient choice. The third picture above is the work room near the bow. Cochise is a big boat so the workroom is incredibly roomy. You can just see one of the central HVAC systems towards the right of the picture.

|

|

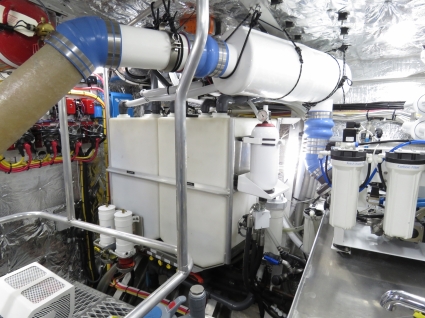

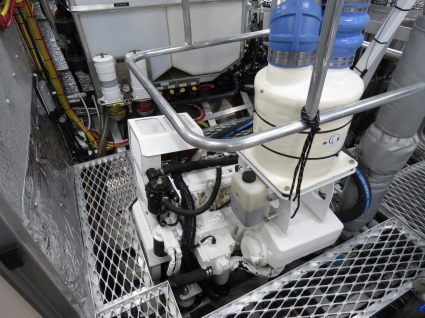

The first picture above is looking forward and slightly right from the back of the engine room. You can see the other John Deere 6068AFM75 and beyond are large waste tanks for gray water and black. The approach to sewage is unusual where the tanks are above the water line so will self discharge without pumps when the valve is open. Because the tanks are translucent, the level is visible at a glance.

The second picture is back in the forward workroom showing the MarineAir HVAC plant.

|

|

In the first picture above, we are looking aft from the front of the engine room showing the port engine, the wet exhaust system, and the engine room fire control systems. The second picture is from the aft end of the engine room looking starboard showing the engine room sink and stainless steel counter with the waste water tanks in the background.

|

|

The first picture above is another angle on the engine room sink, wet exhaust, muffler, and waste storage. The second picture shows the heavily built rudder systems on the FPB 78.

|

|

A view from above the starboard engine looking down in the first picture. The second picture shows the Blue Water Desalination Explorer water maker.

|

|

The key to happy owners and long-lived mechanical systems is engine room ventilation. The first picture above shows the three large axial fans driving the engine room ventilation system. The second picture shows the Onan generator from above.

|

|

James on the starboard side of the boat getting ready to pull in the lines. Steve Dashew is casting off some lines prior to taking us out. If you look carefully, you’ll see the lines are surprisingly light for a 78′ boat. In actuality they are Spectra, a strong synthetic line.

At the right of the second picture, Bill Parlatore is on the bow of Cochise. Bill is the founder and, for many years, the editor of PassageMaker Magazine. Bill now is the editor of Following Seas where he is again focusing on interesting boating topics. We first met Bill at an early Trawler Fest in Poulsbo Washington and we have also written a couple articles for him for PassageMaker.

|

|

The first picture above is of the removable wing control station on Cochise. The wing station provides an excellent view when docking a boat going forward. We didn’t have adequate space on Dirona for a wing station, but really wanted one so we elected to use a Yacht Commander wireless remote control as our wing station. The FPB approach is a removable station that can be deployed for docking and then taken in when not in use.

The second picture is looking aft down the ICW towards the SE 17th Street Bridge. You can also see the large yellow AB tender with a 60 hp Yamaha outboard on the aft deck.

|

|

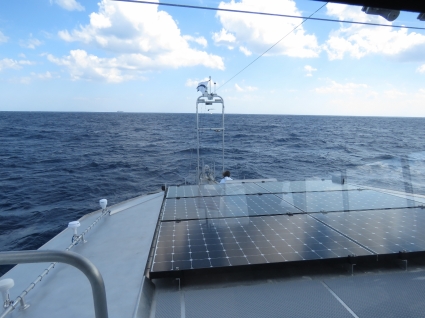

Cochise has solar panels to maintain battery charge when the boat is not in use and to augment the generator when at anchor.

James is at the helm of Cochise in the second picture above. Steve wanted to get some pictures as we were heading in from sea through Port Everglades Inlet to Fort Lauderdale so asked me to take the helm. It was pretty busy that day with many boats in the channel, so I was paying attention. The first thing I noticed was the boat basically didn’t need much in the way of helm input. Certainly its a big boat so others tended to give it space, but the boat also tracks remarkably well requiring almost no helm input to stay heading in on our side of the channel. It’s a remarkably comfortable boat in close quarters.

On a related point, when having lunch in the light to medium swell off of Fort Lauderdale, Steve let the boat drift which is usually not a wonderful choice for a monohull. They typically quickly find themselves a resting point beam to the sea and rolling heavily. Cochise just drifted flat and calm. We had a relaxing lunch and often didn’t even notice we were drifting in a beam sea. The boat tracks remarkable stably and behaves well even when left to drift.

|

|

Continuing the theme of close quarters maneuverability, early on in the cruise I had asked Steve about the bow thruster and was surprised he had concluded it irrelevant and welded the thruster tube closed. He had promised to show me why the thruster really wasn’t useful or needed. In the first picture above, we are heading down a dead end canal running west of the Intracoastal Waterway. The channel isn’t a lot wider than Cochise is long, so turning in this channel is clearly going to require some attention.

In the second picture, you can see Cochise turning in this channel with a 20 kt side wind to add a bit more excitement. I watched the stern fairly closely and we turned in the channel and we had 5 or 6′ feet to give up and Jeff Merrill reported the bow had about the same. For a boat this large, Cochise is remarkably comfortable in close quarters.

The video above starts as lines are cast off and Cochise starts gently backing out of its Fort Lauderdale slip with Steve Dashew at the helm. We eased out into the Interacoastal Waterway and headed south towards the SE 17th Street Bridge before heading out Port Everglades Inlet to sea. The last time I was on a boat heading to sea through this channel I was aboard the USS California, a Virginia class nuclear attack submarine. Clearly this was a very different experience, but both the FPB and the Virginia class submarines are technological masterpieces in their respective classes. The California is clearly much better armed, but the view from the wheel in the FPB was far better :-).

Scott Flanders tying off Cochise as we arrived back at the dock, with Mary Flanders securing lines on the swim platform. The Flanders were on board visiting with the Dashews for a few days. Scott and Mary cruised their Nordhavn 46 around the world and documented their adventures extensively in the widely-read Voyage of Egret. Over the years we have learned a bunch from the Flanders’ adventure and they influenced some of the features we chose on Dirona. I’ve talked with Scott on email numerous times and it was a pleasure to finally meet them both in person.

What a day on the FPB 78. Thinking back on the day on what was most notable, a few characteristics come to mind. It is a remarkably fast boat, always running at over 10 kts on this trip and, at times running as fast as 13.5 kts. Amazing. The boat tracks arrow straight with little helm input and, more surprising, when left to drift without power or helm input in a medium swell. It was super stable with almost no roll. The boat is strong. Leaning against the outboard pile when coming into dock with a strong cross current running south down the ICW didn’t even polish the aluminum. It’s built like a tank. The great room design never gets old. The massive combined pilot house, salon, and galley is wonderful at sea and even better when entertaining at dock. It’s a striking design feature and its one of the first things you will notice when stepping onto an FPB regardless of the size of the boat. All in all, a great experience and a very educational day.

We just saw you on the Delaware Chesapeake canal. You passed the Green Bay car carrying ship. That FPB is beautiful

I agree Cochise is a beautiful boat. That would be Steve and Linda Dashew you saw in the Delaware river. We’re currently in Stavanger Norway.

James:

What an incredible experience! Thanks for sharing.

We are in the market doing research on the used FPB 64’s currently on the market, and also considering the N52’s, given their strong record and your excellent journey. A fast circumnavigation is our goal.

If you had it to all over again, would you choose the FPB over the N52, assuming price for a newer 52 and an older 64 is converging and why?

They are both such different boats, that you’ll likely close on a decision fairly quickly. Each have strong dimensions and their strengths are quite different. Spending time on Cochise was indeed an excellent experience and Steve Dashew is remarkably fun to talk to. He’s very deep in every aspect of boating and boat design and yet still always listening and learning. He and Linda are a lot of fun and we had a great day on what is an incredibly well thought through boat in every detail.

We chose our N52 because it was capable of going anywhere in the world, was big enough to be our full time home, was strong and safe, and remarkably good value for a niche market requirement (ocean crosser). We looked at all boats that had those capability back in 2008 — it doesn’t take long since there are only a handful — and ended up concluding the Nordhavn was our best choice. 10 years later, we still feel good about the decision.

Nice report, James. Great seeing you and Jennifer again. Hope to be back aboard for more thorough photography when she is in NC. Will publish in my FollowingSeas blog.

Hi Bill. It was good catching up with you on Cochise. We’ll keep an eye on your new http://www.followingseas.media boating site. If you are ever in the same city as us, drop by and say hi.

James – I am interested in the all-aluminum construction. I would assume hull must be mostly TIG welded? I can’t tell in some of the pictures. Some edges look to be braked or rolled, but I would assume large panels would be welded. Can you comment on how it is contructed in that regard? I know a lot of aluminum chassis vehicles are using adhesives now as well.

The welding units looked to me like Miller Metal Inert Gas welders but I’m not sure I could tell the difference between a MIG and a TIG unit from a distance. For sure it was all CNC cutting, break press, and welding without the use of adhesives. The weld quality is impressive. Super uniform, little warping on the thin panels, and deep penetration on the thick ones.

Could you comment on how quiet the FPB is underway?

Yes, Cochise is a very quiet boat. Partly it’s just a big boat and the engine is a long way away. But, partly due to the positive impact of many engineering choices ranging from good quality engine mounts, thrust bearing/universal joint drive line, well sealed engine room, and good quality insulation. You can hardly hear the engines running.

Great stuff! I’ve been starting to like FPBs almost as much as I like Nordhavns.

In one of the great room images (Blog_FPB_Cochise_4_IMG_2705.web.jpg), there appears to be chords stretched across the ceiling that aren’t in other photos. Do those serve as removable hand holds for passagemaking? Are they stretchy?

If you were in the market today, would you consider an FPB (assuming availability)?

Good eye to see the ropes stretched overhead on the FPB 78 Cochise. They are hand holds. It’s important in large room designs when at sea to have hand holds. These work remarkably well. When I first saw the approach I was skeptical since rope would certainly stretch and flex and non-stable handholds are almost worse than non at all. Surprisingly the approach is rock solid. A combination of synthetic line with close to zero stretch and them being installed super tight makes the handhold feel secure and it ends up working out very well.

Out of curiosity, do you know how thick the aluminium plate of the hull is? In an entirely different application the Alvis range of light tanks such as the Scorpion and the Scimitar (really tracked reconnaissance vehicles) used aluminium plate about 12 mm thick. Getting the welding right seems key to both applications.

When I commented it was a “tank”, I meant that relative to other boats rather than intending to invite actual comparison with an military tank. The hull plating is definitely less than 12mm although the the the aluminum at the Stem is actually far thicker than 12mm. When I first glanced at the stem of an FPB when walking through Circa Marine, I did a double take. It’s just massive and the boat generally does use uses thicker plate than like sized aluminum boats but you’ll need to get exact dimensions from FPB. I may have been told but don’t recall.

Au contraire, In a fleet designed for toughness, the FPB 78 is the meanest of the bunch. Bottom framing and plating are in excess of what would be considered ice class by Lloyd’s rules from the engine room forward: from the 24mm/1″ thick grounding plate, to the 16mm (5/8”) central turn of the bilge and engine room plate, not to mention the 12mm (1/2”) rest of the bottom. The FPB 78 is available with an MCA Category 0 rating, the most stringent standard under which a small yacht can be built. Although the paperwork is onerous for the builder, the benefits in terms of resale and insurance can be substantial

Sorry, I forgot the link.

http://www.setsail.com/fpb-78-plating-thickness-factors-of-safety-and-emotional-comfort/

Thanks for the excellent link: http://www.setsail.com/fpb-78-plating-thickness-factors-of-safety-and-emotional-comfort/

There is no question, the boat is tough.

Thanks for sharing this James! Your photos really helped give a better perspective on the boat than the ones on the SetSail site. Was impressed by the Youtube video of the FPB in heavy seas. Hope you and Jennifer are enjoying the warmer weather.

Yes, we have been enjoying the weather and will for another couple of weeks here in Florida before starting to head north again. Next stop is likely Savannah GA before continuing up the eastern seaboard.