Watchkeeping is one of many important considerations when planning for an ocean crossing or a multi-day passage. Single-handers have little choice but to sleep while underway, with no-one monitoring the helm, while crews of at least two have more options. And the appropriate watch schedule will vary greatly depending on the number of crew, their sleeping habits and their individual safety goals. Some people can sleep at any time of day, or for short periods at a time, while others have difficulty adjusting their circadian rhythm or need more sleep time.

Our chosen operating mode is to always have someone at the helm, but our watch system and schedule has evolved substantially over our five ocean crossings and numerous multi-day runs.

Watchkeeping Schedule

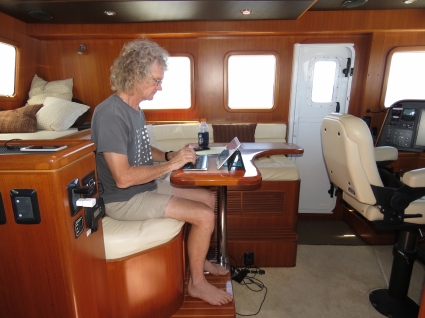

For several years, we followed a four-hour watchkeeping schedule as described in 24×7 Rhythm: Watchkeeping. We ran a formal night watch schedule of 3 4-hour shifts between 8pm and 8am. Jennifer took the first and last shifts, and James took the helm from midnight to 4am. We had breakfast, lunch and dinner together, with Jennifer sleeping for 2-3 hours between meals, and after dinner started the formal night watch shifts.

This model worked, but there were downsides. When you are running four hours on four hours off with a two-person crew, there really isn’t time to talk. It feels sort of like you are alone on the boat and we really didn’t like that. A closely related problem is we were always tired. Never dangerously so, but just always quite tired. This isn’t ideal under any conditions but, in the few times we have run into mechanical problems, being tired removes some safety margin while we work issues. And James found it hard to get his day job done (he continued working full-time on passage). Overall, four-on, four-off is conventional and functional, but neither enjoyable nor likely the safest solution for a two-person crew.

|

|

| James continued working full-time on passage and had difficulty getting his day job done in the four-on, four-off schedule. | |

The schedule also worked particularly poorly for us on shorter passages. Until we got into the watchkeeping rhythm, James rarely was tired by 8pm and had difficulty going to sleep on his 8pm off-watch, so ended up not sleeping much during that first shift. And if we arrived first thing in the morning, Jennifer only got 4 hours sleep between 10pm and 2am. So on an overnight or two-night trip with a morning arrival, we’d each end up sleep-deprived and unable to fully enjoy the first day at our new location.

To address these issues, we experimented with a different watchkeeping schedule on an overnight run from Tasmania to Melbourne. After an early dinner, James took the helm from 6pm to 10pm while Jennifer slept. By 10pm James was tired and ready to sleep and Jennifer, who generally can fall asleep at any time, had slept well. She then took the helm at 10pm with the plan to stay on watch as long as possible, hopefully at least six hours, but to wake James up when she was feeling too tired. Surprisingly, she had no trouble remaining on-watch all night. James was well-slept and ready to go, Jennifer got a good sleep before arriving, and we had a great first day in Melbourne.

This became our new watchkeeping schedule that we have maintained ever since. Effectively, James has the helm from 5am until 10pm and then gets seven hours of unbroken sleep while Jennifer has the night shift. After an early dinner, Jennifer has a formal sleep shift from 6pm to 10pm and then again from 5am for as long as she likes, usually until around 10am. She now gets two longer sleep shifts instead of three smaller ones, for at least eight hours.

|

|

| In our new 2-shift watch schedule, Jennifer has the helm from 10pm until 5am and James has the other 17 hours. | |

The schedule resolved all our issues. We’re well-slept during the passage, we arrive ready to explore, James is super-fresh to tackle issues if we have a mechanical problem, and has plenty of time to get his full-time job done. We also enjoy spending more time together on passage. On the previous watch schedule, it felt like one of us was always heading to sleep and we hardly spent much time together. In this model we have lunch and dinner together, and the time in between those meals. And should anything on the boat require attention, we can handle it without chewing into either of our sleep shifts.

Automation

One of the ways we keep the overhead of watchkeeping to a minimum is through automation and reliability. The less work we have to do during our watches, the less fatigued we will be. We do full engine-room checks between shifts, but having to constantly check and monitor the boat for issues while on watch is tiring, and it’s easy to miss something. Instead, we rely on our automation systems to provide early warning of problems or unusual conditions. We want it to be easy to use even when we’re tired or managing difficult weather.

Maretron N2kView is a good-value display system that has worked very well for us and allowed us to incrementally expand what we monitor over time. This system monitors the NMEA 2000 communications bus to give us visibility into almost every instrument in the entire boat, including navigation equipment, weather instruments, main engine, wing engine, generator, depth sounders, inverters, chargers and pumps.

|

|

| Our Maretron N2kView underway display allows an easy first-level scan for non-green lights. | |

Above is the display we normally use when underway (click any image for a larger view). The displays can be configured almost any way desired. It looks complicated, but in fact the first-level read is just scanning for green lights at each gauge and checking there are no yellow, orange, or red indicator lights. As long as we’re seeing nothing but green lights we know the boat is in good shape and everything’s functioning properly. It’s an easy quick check that we can perform quickly and frequently even when tired.

If something goes wrong we want to know immediately and have more information at our fingertips. If an indicator light goes to warning, it’ll get noticed quickly and the detailed data to more fully understand the problem is immediately available in a gauge, graph, or numeric display. And if for some reason we don’t notice the indicator light, an alarm eventually will sound to alert us. More detail on our system is at Maretron N2KView on Dirona.

Watch Alarm

Human error is the mostly likely problem on any trip, either from falling asleep or becoming distracted. To mitigate this, we have a watch alarm where every 10 min the person at the helm has to touch a switch that is not reachable from the helm seat. When pressing the button, we do a full scan of the instrumentation and a visual scan forward. Having the switch unreachable while seated at the helm is important. We know of several fish vessel groundings where the person on watch was effectively asleep but able to reach and press the switch without waking up.

|

|

| The watch alarm switch should be unreachable while seated at the helm to prevent resetting it while effectively asleep. | |

The system shows a countdown to alarm, with a yellow warning light at 10 minutes, a red error light at 11 minutes along with a single small beep, a continuous alarm at 12 minutes that would be difficult to for the watch-stander to miss, and finally a continuous wake-the-dead alarm at 13 minutes that would wake up the watch stander on any boats in the area and would be absolutely impossible to sleep through under any circumstances.

|

|

| Our custom watch alarm, circled in red at left and enlarged at right. We particularly like having a countdown visible and lots of warning before the alarm triggers. | |

We initially used a Watch Commander Pro to achieve a similar functionality. But it failed on the Indian Ocean crossing, so we created a better version of it using a Raspberry Pi. In our custom system, we particularly like having a countdown visible, and lots of warning before the alarm triggers, so we know if we need to press the button before using the head or getting a snack from the galley, and have plenty of time to react of we do miss it. The Watch Commander had only the 30 seconds of warning available with no visible countdown. Avoiding triggering the alarm was a bit more of a chore, with an increased risk of unnecessarily setting off the audible alarm.

|

|

| The Watch Commander Pro alarm that we used for the first three years. | |

Sleeping Location

Dirona is equipped with an off-watch berth behind the settee in the pilot house, and this is where we initially slept on overnight runs. We liked the off-watch berth, and occasionally use it for naps during the day, but found its intended purpose didn’t quite match our operating mode and we evolved to using the master stateroom for our off-watch sleep periods.

.web.jpg) |

|

| We initially slept in the off-watch berth while on passage, but evolved to using the master stateroom. | |

Having the off-watch person nearby initially was convenient, and felt safer, as we were learning to run overnight. But we quickly found several disadvantages. The first was that this made being on watch more difficult. The person at the helm had to be incredibly quiet moving around or preparing a snack in the galley. And we needed to ensure noise in the pilot house was minimized. The volume on equipment such as VHF radios must to be low to avoid occasional sudden loud static, requiring the person at the helm to monitor the radios very carefully. And we also had to pay close attention to the watch alarm to avoid it making even the smallest warning beep. In calm conditions, this wasn’t such a big deal, but in rougher weather, being on watch can be surprisingly tiring. Even the small effort needed to monitor the pilot house equipment felt like a lot. And invariably, no matter how quiet we were, we ended up waking up the other person, or at least disturbing their sleep.

|

|

| Sleeping in the master stateroom reduced the on-watch effort of restricting noise in the pilothouse. | |

Sleeping down below in the master stateroom was a vast improvement, and we didn’t feel we were giving up anything with less proximity to the helm. We have a monitor beside the master berth that mirrors whatever is displaying on any of the four pilothouse screens. So if the person off-watch is at all concerned, they can simply glance at the screen without fully waking up. We initially also had a VHF intercom radio on the master to communicate back and forth if needed. But we didn’t use it much and eventually removed it.

|

|

| The off-watch person can easily see any of the four pilothouse screens from the master berth without fully waking up. | |

Another problem with the pilot house off-watch berth is that it is much higher in the boat than the master berth, where motion is exaggerated, and is oriented athwartship. If we are in pitching seas where the stabilizers cannot help, the person sleeping slides from side to side, making sleeping difficult. And in heavy beam seas, where the stabilizers can get overwhelmed, the sleeper slides between the head and the foot of the berth. The master stateroom in the Nordhavn 52 is oriented along the center line and is much lower in the boat than the pilot house berth, very close to the center of gravity, so there is remarkably little motion in the berth.

|

|

| The master stateroom berth has much less motion than the pilothouse off-watch berth. | |

The master stateroom worked remarkably well under most conditions, but when the seas are at all rough, we’ve learned to sleep wedged in the narrow floor space beside the bed. The motion there is a lot less annoying and we sleep far better. Using that trick, we find it takes quite rough conditions before we start having sleep problems. This also avoids the risk that befell James years ago where a bigger wave tossed him out of the berth and into the head doorway frame. Sleeping on the floor looks a bit odd, but it ends up being a surprisingly comfortable way of dealing with rough conditions.

|

|

| When the seas are at all rough, we sleep wedged in the narrow floor space beside the bed. | |

Summary

With our watchkeeping systems, if the weather is good, we can be on passage forever and don’t arrive tired. If the weather is rough, there really doesn’t seem to be a good solution. We just end up less well rested when operating in rough weather. Most of our crossings have been at favourable times of the year and we really haven’t seen that much rough weather. Having crossed all the oceans and the Atlantic three times, with only two people on the boat, we’re impressed with how comfortable the boat has been, and the systems that we’ve evolved have made it the adventure pretty easy.

Related posts:

| Dinner underway from Cape Town to St. Helena. With our current watchkeeping systems, if the weather is good, we can be on passage forever and don’t arrive tired. |

If your comment doesn't show up right away, send us email and we'll dredge it out of the spam filter.