.jpg)

River bar crossings require great care and in some conditions they simply can’t be safely crossed. Earlier this week, the crew of the commercial fishing vessel Mary B requested help from the US Coast Guard in a night crossing of the Yaquina Bay bar at Newport, Oregon. Sea conditions were reported to be 14 to 16 feet with occasional 20 footers. Asking for a Coast Guard escort is a fairly common practice when crossing dangerous river bars along the US west coast. In fact, in some conditions the Coast Guard closes the crossing entirely and boats must remain at sea or in harbor until the closing is lifted. For example, when we crossed the infamous Columbia River Bar, pictured at the top of this post, it has been closed up until an hour before we arrived.

In this case, the Coast Guard 52-ft (15.8 m) motor life boat Victory went out to meet the Mary B. While the coast guard vessel was nearby, the Mary B capsized just after 10pm. The Victory immediately started searching for the crew members of the Mary B and called for assistance. A Coast Guard 47ft (14.3 m) motor lifeboat and a MH-65 Dolphin helicopter were dispatched from Newport. The Newport Fire Department also were notified and sent a team to search the shoreline.

The Mary B was located in the surf about 100 yards from shore. 1 hour and 22 minutes after the capsize the first body was recovered. A second body was recovered by the shore-side team. The third and final member of the crew was spotted inside the structure of the boat still 100 yards off shore but conditions were sufficiently poor that recover was delayed until the following morning.

It’s always sad to see lives lost at sea. What’s notable about this event is it’s just about impossible to have access to better life-saving skills than the US Coast Guard and they were actually right on scene. A fully crewed 52-ft motor lifeboat was only yards away when the Mary B capsized. The lives were lost with immediate access to some of the best trained and best equipped rescuers in the world. It underlines, more than anything that we’ve seen, that bar crossing is dangerous and is a decision that needs to be made carefully and conservatively. It’s easy to say “the crossing shouldn’t have been attempted” and, knowing the result, it’s hard to argue with that perspective. But, for those that haven’t been there, needing to make one of these decisions, over-simplifying is easy.

It’s very difficult to assess wave size and danger from the back of the wave. The sea side of the wave always looks much safer than the shore side. Without significant experience reading waves, it’s easy to make the wrong call. It’s also easy to underestimate how poorly boats can handle in breaking waves. The Coast Guard practices constantly off the Columbia River and the videos of them totally inverting a 47′ motor lifeboat with the crew holding on and popping up to continue while hardly losing speed is absolutely amazing.

Most boaters and even some professional fisherman haven’t had this experience and some of us aren’t sure we want it. Without experience, you may not accurately know what your boat can do. Finally, conditions well within the capabilities of the boat can rarely produce a set of far bigger waves. Even a good, experienced decision that was well within the capabilities of the boat could be catastrophically wrong if a larger set of breaking waves arrive unexpectedly.

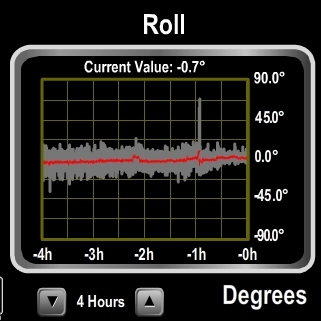

That’s exactly what happened to us in our Wide Bay Crossing (69.1 degrees). Wave conditions were difficult, but not close to the ability of the boat. They weren’t really even all that uncomfortable. The route in was clearly visible and there was no breaking water. During the transit, a bigger set of waves arrived and there was a solid line of breaking waves behind us. When those waves hit, the 55-ton Dirona was knocked on her side at 69.1 degrees, we took on more than 1,000 gallons of water into the engine room, and many on-board components were damaged. For full details on our Wide Bay Bar crossing see 69.1 degrees.

Experience helps. When we faced the same decision with far smaller waves returning in the dark to the Netherlands at Terschelling from Germany, we decided not to make the crossing. Because we run powerful forward lighting, we could see the waves were breaking. We now have enough experience in breaking waves to know what’s manageable in Dirona and what’s difficult, and elected to turn back. But making these calls with accuracy is super-difficult, particularly at night. Without bright, forward lights, you won’t have the information you need. Reading the back of waves (sea side) is difficult. And many people don’t know how their boat will manage in large breaking waves. Certainly experience helps but, even then, it’s a tough call with a lot at stake.

This sad situation is a reminder to us all of the danger of breaking waves in small boats. With some of the world’s best marine life saver’s right on hand, lives were still lost. It’s a reminder to be conservative on these breaking water decisions, to remember that things can go bad in a hurry, and that if things don’t go well rescue may not even be possible.

For more details on this incident, see the excellent gCaptain report Three Fisherman Killed Crossing Yaquina Bay Bar in Oregon.

Thanks, James, I notice that the current Nordhaven “Video of the Month” features N68 Sanjero on a passage from Brisbane to Hamilton Is. Shown at around the 1m 50s mark , their crossing of the Wide Bay Bar was a much more pleasant experience than yours. Perhaps a good example of how variable bar crossing conditions can be.

Ironically we have never been through Wide Bay Bar but we almost did once :-). Like all river bars, most days are good days but the bad ones can be exciting.