We bought an ocean-capable boat not because we were convinced we would round the world, but because we wanted the flexibility to be able to go anywhere in the world if we wanted to. We bought a strong boat not because we were convinced we needed to test it, but because we wanted a boat with “engineering headroom” — we wanted it to be considerably stronger than the worst we were likely to ask it to operate through.

Five years later, it turns out it’s a good thing we decided to accept the various compromises that come with an ocean-capable power boat. Who would have guessed that, as we type this, we’re anchored on the outer edge of the Great Barrier Reef in Australia with dreams of still ranging further afield. And, looking at the other attribute we value so greatly, boat strength, it’s not one we expected to test and it’s certainly not one you want to test. But Dirona has done fairly well by that measure as well. We have seen no survival storms — fortunately they are rare and modern weather reporting can avoid the worst of them except in statistically anomalous situations. But they can happen, so we wouldn’t sacrifice strength for anything. Just two people out in the ocean 1,000 miles from any shore can make boat strength feel like a super important attribute even though it is seldom tested.

We have seen some tough weather but most of it was actually surprising close to shore. Ironically most boat operators are extra-careful in selecting the weather and time of year when making ocean crossings so it’s little surprise that the worst conditions experienced by recreational boats are often near to shore. For us, memorable times are fully developed seas in 40 kt wind in the Gulf of Alaska with gusts as high as 59, the east coast of New Zealand north of Wellington in only 30 to 40 kts, and the east coast of Australia in the shallow coastal waters of the Tasman Sea near Brisbane in around 40 kts. None of these conditions were particular dangerous or even scary but they were onerous and sometimes a bit tiring. Having a good strong boat can transform the potentially scary to only tiring. And, there is no question, compared to the stories you hear from local fisherman and professional mariners that are out there all the time in these areas, we have seen close to nothing on board Dirona.

One notable test of the boat did happen fairly recently in attempting to cross the Wide Bay Bar south of Fraser Island on the east coast of Australia. In all the conditions we had seen prior to this event, we have managed to avoid large breaking seas. It’s in these conditions where weather conditions swing from taxing to dangerous. Massive breaking seas can happen in extreme conditions, but are especially frequent where high winds meet large ocean currents (e.g. the Agulhas Current near South Africa). Fortunately, these conditions are fairly rare and largely avoidable. One place where these conditions are actually fairly common are river bar entrances. In the US, the entrance bar of the Columbia River is particularly renowned for producing harrowing conditions — in fact, the US Coast guard trains rough water small boat handling there — but nearly every maritime country has their example. In New Zealand, the Grey River Bar has really earned its notoriety.

River bars can be dangerous and anyone with sea experience knows to avoid them if the conditions aren’t right. But, estimating when the conditions aren’t right isn’t as straight forward as one might think. For example, we crossed the Columbia River bar where, just 1 hour before, the US Coast Guard had it closed to all recreational craft. At the time when we actually crossed, they were only allowing boats through that were over 50′. We braced for difficult conditions but actually found it an unremarkable crossing.

Recently, when faced with the same decision here in Australia, it was clear that conditions were worse than our Columbia River bar crossing, but with the wind blowing a steady 30 to 40 kts and it being nearly 100nm to another anchorage, there is a clear appeal to crossing the bar. The conditions were not expected to improve for 3 days. Nonetheless, we’ll take 100 nm in rough water over dangerous conditions all day, any day. Before approaching the Wide Bay Bar, we read all we could on the bar crossing and what to expect. We radioed Coast Guard Tin Can Bay to get the latest GPS coordinates since bar conditions can change over time and the Coast Guard often has current bar conditions. They said nobody has crossed that day but they did expect it would be rough and speculated it must be rough out where we are as well. We agreed, it definitely was lumpy. They said we might be happier in than out but neither would be easy right now.

At this point, we felt like we had all the information available on the bar crossing as we approached it from seaward. There are two aspects to sizing up bar condition from sea that make precision difficult. One, is turning around and returning to sea can be difficult and the other is the back side of waves driving onto the shallows always look much smaller than they do when looking from the landward side.

A good data point is to watch the waves beside and just forward of beside the boat. These were towering breaking waves off just 50′ to the right and the same to the left of Dirona. But as we slowly inched into the shallows, there were no breaking waves across the 100’+ entrance path. The waves were big, the water was incredibly churned up further in, but the line of breaking waves had a clear gap along the entrance path. Our read of the conditions were that they were difficult but crossable and we proceeded further in. We were watching behind us as much as in front as we followed the recommended crossing path. Conditions ahead continue to look random and churned up and the waves beside us were breaking and dangerous, but we continued to work in on large but not particularly frightening waves. We keep the boat centered on the entrance path and continud to look both forward and back as we proceed shoreward. A particularly large wave was building behind us and it seems to just keep getting bigger. What was a big concern is the non-breaking section behind us was closing up on this wave and it’s starting to break all the way across. Because we are traveling in the same direction as the wave, there is actually more time than you would guess to watch the non-breaking gap close up behind the boat. The wave just kept climbing as it neared us, starting to lift Dirona at the base of the wave. We rose about 1/3 of the way up the wave as it passed underneath before getting hammered by the break from above. Water power is simply incredible.

Dirona was driven back down the wave by the breaking section fast and, as we headed down, the stern very slowly accelerated more quickly than the bow and started to swing off course to the right. We now were at full throttle and full right rudder, but the stern continued to get driven around the forefoot towards the starboard side by the breaking wave from above. The boat rotated broadside into the wave, the wave continued to drive it down and the boat slowly rolled away from the wave. At this point we could hear the furniture “pouring” into the starboard side of the boat. We didn’t really feel that far heeled over but gravity definitely was creating a mess in the salon behind us. When the wave had passed, the boat was popping up, but the wave’s twin was close behind and also breaking. We turned the boat back towards the shoreward path we were on earlier as the second wave hit hard from above.

As the second wave passed, we are fully upright and back on course. I was pretty confident we could continue through the random choppy seas forward and safely make it through the channel. Essentially, we’re back upright, on the right track to proceed, and it appears we have seen the worst. But, there were now alarms going off all over the place inside the boat. Forward still looked better than backward at this point. I quickly checked both the main and wing engines and both were fine. I briefly though I’d I’ve lost steering but it was just the steering follow-up lever and the steering was fine as well. All mechanical systems were OK and, as I scanned the instrument panel to figure out where the alarms are all coming from, I said to Jennifer I think we’re OK to head in with no further breaking waves appearing to be forward. We could now see that we have many bilge water alarms firing, and I knew the auto-pilot follow-up lever was no longer working. We have an old rule that has stood us well over the years: “if in difficult or dangerous situation and a systems fault occurs, abort the trip and find a safe spot to correct the issues”. The logic here is that most disasters are not a single mechanical or human fault. More often than not, life or property is lost when a chain of failures happen where each builds on the other. So, very reluctantly, I swung the wheel hard over and used the thrusters to rotate the boat 180 degrees and put the bow back into the seas before the next one hit.

Understanding the source of the alarms, ensuring mechanical systems good, and making a decision to leave felt like it was a fairly long process but it was actually only the tiny space between the second and third breaking wave. The third wave broke as we rode slowly up to the top, crested, and then fell deep into the trough beyond. The boat felt perhaps a bit lethargic but, with the waves on the bow, these waves were not really much of a concern.

I also had the hydraulic emergency bilge pump on, since both the high water and the main bilge pumps had run flat out since the knockdown. By now, I’d accepted all the alarms, there was finally quiet, and things had settled down to something closer to normal. I looked down into the salon from the pilot house and the furniture was piled up in the forward, starboard corner of the salon up against the day head. Clearly there would be some damage down there.

The boat now felt fairly secure as we took the 4th breaking wave without issue and the next one looked smaller either because the over-large set had passed or we were getting more depth under us. So, I left Jennifer with the helm and ran down to the engine room to check on the bilge alarms. The bilge was completely full and the water was about 6″ above the engine room floor and about 2″ up onto the bottom of the main engine oil pan. Not good. I was starting to worry about where it all was coming from and whether we might have an even bigger problem. I ran back up to the pilot house to make sure all continued to be well. It was, so I went back down to the engine room and the water. The water was now down below the floor boards, leaving behind a surprisingly large amount of dirt and organic matter. I ran back up the pilot house to find things still under control, and back down to the engine room. The main bilge was now close to dry but the forward bilge drain into the main bilge was plugged with sea-born debris and wasn’t making much of a dent in the forward bilge water levels. I cleaned out the drain from the forward bilge down into main bilge, and the water flowed down in seconds and was ejected just about instantly by the hungry hydraulic emergency bilge pump.

The boat now was fully dewatered by the hydraulic bilge pump. It’s an absolute beast and is able to pump 100s of gallons per minute. In testing, it can send a 2″ jet of water across two slips! It can pump a silly amount of water. I have always loved this piece of safety equipment but my fondness for it grew considerably over those few minutes. It was just wonderful to see the water level falling, proving it’s either not a problem or, if it is a problem, the safety equipment had the clear upper hand.

The boat was now back to 100% operational. There was no water in the engine room or the bilge and even the “failed” steering follow-up lever was back and fully operational. Apparently the follow-up lever always was fine but the aft helm station had “taken control” during the knockdown probably due to sea water closing the “take control” switch contact momentarily. We ran the short distance to the Double Island Point anchorage where we joined three other boats attempting to wait out the worst of the storm. We took a safe spot in the anchorage and cleaned up the boat and inventoried the damage.

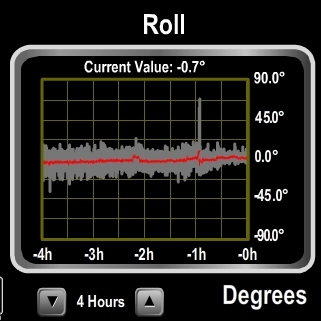

In taking stock of the situation, we were surprised to learn that our sat compass system had measured the boat over at 69.1 degrees. It really didn’t feel like that much. And, I suppose, for the old sailing hands out there it really wasn’t all that much — many have seen a knockdown or two. But, as a point of reference, Dirona has never, even in the worst conditions, been heeled over more than 30 degrees so it seems like an awful long way over to us. Because the waves were breaking from so far above Dirona, we took stresses all over the boat.

The dinghy is held down by heavy-duty trailer straps, and the nylon strapping on one had parted and the dinghy had shifted in its chocks. Our aft deck furniture was folded up and attached to the starboard side of the cockpit with the same type of trailer straps. One was stretched so far, the stainless steel latch no longer closed.

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

The hydraulic pressure was so high in the cockpit and starboard walkway that the forward deck boarding hatch barrel bolt was bent outwards and no longer operative.

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

Even more surprising, the aft cockpit boarding door latch had completely sheared. The first picture below shows the broken latch, and the second picture is after we replaced it.

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

Apparently when the door blew open, it then latched open. Then later hydraulic pressures tore that latch out as well.

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

Two of the five LED strip lights, along the starboard walkway, were destroyed by the water pressure. And the two overhead lights in the walkway filled with saltwater and failed quickly from corrosion.

The galley flower vase, stowed in a port-side basket behind the salon furniture, shattered as it hit the starboard-side settee. And one drinking glass broke. There are three sets of scratches on the woodwork in the salon from furniture in flight. I hate seeing a blemish or two in Dirona‘s woodwork but, in the end, I suppose it’s nice be surveying minor cosmetic damage. There really wasn’t much damage at all.

It’s unlikely, given the location of the engine intake grills (4 or 5 feet above the waterline and set to the inside of the boat in first picture below), that it was ever underwater. But we still managed to take on hundreds of gallons from the onboarding wave through the starboard intake grill. The two engine room cooling fans on the starboard side failed a day later due to sea water ingress but, throughout all this stress, everything kept working during the time of the event.

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

The boat popped up like a cork as soon as released by the breaking wave, everything kept running, the safety equipment did what it was supposed to do, and as soon as we were bow to the waves again, it wasn’t even particularly difficult to manage even with breaking waves. The list of faults we did take is not insignificant but it feels like a bunch of minor scrapes and nicks.

We feel like the boat did really well and, as we reflect on the situation, the first things that jumps to mind is we are glad we got a strong boat. Money spent on strength sure feels well spent and giving up speed or interior space for strength feels like a bargain. The next things is that breaking waves can happen anywhere and are in no way restricted to bar conditions. Bar crossings produce them with frequency but breaking seas can be found across a wide set of different circumstances. The obvious learning is to avoid them but there may be times when you do find these conditions. Knowing how the boat manages them is important. For Dirona, the boat seems most comfortable bow into the weather in survival conditions so, if we ever do find ourselves in breaking seas in the open ocean, we will get the bow into the waves to ride it out. Looking specifically at river bars where these conditions are common, we have long known that waves appear smaller from the backside than from the landward side. So it’s important to keep this in mind when assessing conditions. It’s difficult to turn around fast enough in a narrow channel between big waves so it’s important to make the decision early enough. And, what we learned in this case arguably we already knew but this certainly drives it home, wave sets vary greatly in size. If there is a respectable period of non-breaking water in a channel, it doesn’t mean that you won’t find a larger set of waves when transiting. We would have been well served by studying this entrance for longer from seaward since breaking seas can be so dangerous.

More than anything, this experience drives home the point that can’t be made often enough. If water doesn’t get into the boat in large quantities, you can survive incredibly bad conditions. And, unfortunately, even very safe conditions can be life threatening if water does get into the boat. I’m an engineer at and I read extensively about engineering disasters mostly because it’s my job to avoid them. Knowing how others fail can help me build systems less likely to suffer the same fault. I do the same thing around boating and read extensively about boat losses and faults. It’s absolutely amazing how many fish boats have been lost to a broken pipe underwater causing flooding, or a house door left open as the trawl door pulls the boat over, or a pilot house door open as the boat gets hit by a particularly large wave.

On Dirona, we have a policy of having the boat sealed up without windows or doors open when operating in difficult conditions no matter how hot it is. If doors were open in this event, the boat clearly may have been lost. That’s the same reason we use the storm plates to protect the larger windows on longer crossings. A broken window can sink a boat in difficult conditions. We did take in 100s of gallons through the engine room air intakes but I’m not sure how I would recommend designing them better. They are very well placed on Dirona and I’ve had many a fisherman look longingly at our engine room intakes commenting they like the placement and height. I’m not sure how to avoid the few seconds of water ingress we did get. What I like is the water was kept away from the equipment and was quickly ejected by the emergency bilge pumps. Having silly large capacity dewatering pumps is a worthy addition to any boat. On Dirona, we have all the standard pumps, and Nordhavn is quite generous in this dimension, and we also have the optional hydraulic bilge pump and a portable Honda crash pump that does double duty as an emergency dewatering pump and fire pump.

Another policy we have, that certainly limited the damaged we sustained, is that the boat is always ready to go to sea. The few large loose items we have, such as the deck furniture, are easily stowed. We have heavy-duty latches on all appliance doors and any heavy drawers—the small push-button latches are fine for moderate conditions, but will not hold in rough seas. When we heeled over at the Wide Bay Bar, several minor items on the port-side guest stateroom berth were launched to the desk on the starboard side, skipping the floor entirely. If we didn’t have the heavy-duty latches on the large, heavy drawers underneath the berth (second picture below) those drawers would certainly have been ejected, resulting in considerable damage.

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

After a night in a rough anchorage with 3 other boats to sit out the storm, we woke the next day to find our 1″ anchor chain snubber with ballistic nylon anti-chafe had parted in the over 50 kt gusts. But it was likely the 3′ to 4′ swell rolling through the anchorage that loaded the snubber to the point of failure. That morning at high tide, we went back to survey the bar conditions. There was no question they were better than they were the day earlier but, with breaks very near the channel and fairly big water across the channel, we elected to do the 100+ nm run around the north end of Fraser Island.

The Fraser Island and Great Sandy Straits area really is an amazing cruising ground and we really enjoyed our time there. One particularly interesting day, we were anchored for the night just inside the Wide Bay Bar and walked over to the other side to watch the waves pound in from seaward. Over a nice picnic lunch on a windy but sunny day, we remarked how much bigger the waves look from the shoreward side. It was exciting to watch them crash in over lunch.

|

|

.jpg)

.jpg)

Great Article. Ian Oric raised the same point I am interested in, did you think of using a drogue?

It’s a good question. In this specific circumstances, a drogue would be difficult to use due to the shallowness of the water. It’s under 15′ at this location but, in thinking through the general question, I would think yes. The boat was very stable with the bow into the waves on the way back out and I suspect if the stern was held back by the drogue rather than being driven around and rotating the boat sideways, the boat would not have been forced over onto it’s side. I think the drogue would be effective in high water, open seas conditions but still wouldn’t be practical in narrow channels.

Trying to figure out where that ‘trash’ pump is going. If down deep in the engine room, isn’t it going to be flooded out? Certainly they don’t seem to be designed to run under water. When you say ‘hydraulic’, are you talking about some type that runs off the engine? And what starts that pump? Some type of float switch?

There are many pumps. We have 2 Rule 3700s, one of which is down in the bilge. They are on float valves these pumps will run fine under water. The hydraulic pump is mounted higher in the engine room and it’s a manually switched pump (needs to be turned off/on). This pump is also not self priming so the operator needs to avoid running it dry. Both the main engine and the wing engine can drive the hyraulic system and either is sufficient to fully operate this hydraulically operated pump. Technically the hydraulic pump will work fine underwater but it’s high enough in the ER that, if it’s under water, the boat may have already sunk or will be getting very close.

There is a gas fueled Honda crash pump that we maintain for emergency bilge pumping and last ditch fire fighting.

There is also a hand operated manual bilge pump if all the electric, hydraulic, and gasoline powered pumps fail. The lower Rule 3700 automatic bilge pump pumps through the manual bilge pump. Neither provides a significant resistance to the flow of the other and I would never use both at once. In fact, I’m skeptical I would ever use the manual pump but it’s still in place. When the rule 3700 is running it’s pumping from deep down in the main bilge through the manual pump. If the manual pump is used it’s pulling water right through the Rule 3700. I’ve tested both and both work without material reduction in flow as a consequence of this serial installation.

The boat has a hydraulic system where hydraulic oil is delivered at 3,800 PSI from pumps on both the main engine and the wing engine. This hydraulic system powers the active stabilizers, the anchor windlass, the emergency bilge pump, and both the forward and aft thrusters. Either engine can drive any single device fully and the system is sized such that both thrusters can be driven fully together. If either engine is running, then the hydraulic bilge pump can be turned on.

The trash pump is a gas powered Honda that with around a 12′ intake hose that can be placed anywhere and then a long delivery hose that be put overboard or a nozzle can be attached and used to fight fires as well. Clearly before using salt water to fight fires, we will have exhausted all lower risk and less damaging alternatives.

The rule 3700 and the hydraulic bilge pumps all work fine under water although the hydraulic pump is mounted sufficiently high in the ER than it would only see water if the boat was going down or very close to it.

Could do without some of this excitement, but it raises a question:

Thinking about water ingress though engine air intakes makes one wonder if some simple shut-off systems such as appear in rudimentary snorkel equipment couldn’t be employed. Let a flapper or somesuch close and let the air come in from the opposite side intake or through the engine room itself for the moments of inundation.

Has anyone attempted this?

The best solutions I’ve seen is to bring the intakes up higher. Many larger ships put the intakes in the stack such that they need to be very close to 90 degrees before they suffer water ingress. I’ve not seen a system where intakes are shuttered closed but this is done for fire control so it wouldn’t surprise me if the system has also been used to reduce water ingress risk as the boat rolls.

Generally, the Nordhavn solution is better than average. It can take on water if the boat gets much past 60 degrees but that is a long way over.

James,

I have used Ian’s reversing technique in a low powered 12 ton yacht. We crossed the dangerous Port Macquarie bar on the NSW coast when it was breaking. It seems counter intuitive to go as slow as you can, and reverse when a big wave catches up but it really worked for us. The waves just broke around us. I don’t know how it would go with a large open aft cockpit but it could be worth trying the technique in less extreme conditions first.

Cheers,

Richard.

If we had known that conditions where going to be breaking straight across behind, we would have just waited or gone around the island avoiding the bar. As we approached it, there were no breaking waves in the channel. However, assuming we are in the position of needing to cross a bar with breaking waves, I can confirm what you are saying seems to be true of our boat as well. When hit on the stern by a breaking wave even under high power it was pushed around and over. We turned around and, with the bow into exactly the same waves, the boat wasn’t even difficult to handle. Backing in would feel very uncomfortable but the boat seems very stable bow into the waves. My take away was, in survival conditions at sea, bow into the waves is the best way to get through the storm on this boat.

Fabulous article. Wide Bay Bar is an absolute mongrol in crook weather. I had much the same issue as you in a 48’ motor sail. I travelled slow and clutched astern as the big roller came thru at about 15-17 kts. Saved our bacon!!

Backing in sounds like a good plan. Once we had bow to the waves, the boat was much more stable. As we approached there were not breaking waves all the way across but a bigger set came through knocking us down while we were crossing.

Wow, that was a little more heart-pounding than your typical entry, to say the least! (Not that “A more flexible power system for Dirona” isn’t thrilling reading, but, well, you know…) We have experienced a similar event entering Sebastian Inlet on FL’s East Coast (beware Monster Hole!), and I hope we have learned enough from that, and now from reading about your experience, to never have to go through it again.

More exciting than “A More Flexible Power System for Dirona?” No way Brian. You know, looking back at that event where Dirona was over on it’s side, it’s amazing how little damage there was. The latching hardware in three exterior boarding doors broken, a couple of ER fans, a hold down for the tender, the crane drive motor and, wouldn’t you know it, the spare as well -). A couple woodwork dings in the Salon from the furniture landing on the walls but, generally, not much at all.

Log that one under the category “That which doesn’t sink you makes you smarter”! (And if it doesn’t cost much to recover from, all the better.)

Hi James, as a new unexperienced loving nordhavn boater I am reading your blog with much interest. I see that you took water by the ER air intake. While I am not an expert and I do not know exactly how these air intake are built on your boat I think the risk of seeing issue again can be easily mitigated. I’m just speaking here so don’t mind me if I make some silly comments but I guess these air intake are direct intake if so much water came in. An easy and simple solution would be to have a S type intake where the intake channel in making an upper S above the intake grill. This simple design would allow water flow inside only in the case where the water level would be above the higher point of the S what would mean that the boat is totally submerged. Not sure I clearly depict what I think but hope you will understand :)

Your suggestion is a good one Lou and, actually, the Nordhavn air vent design is a pretty good one. The air is taken in 6′ above the water line in vents in the cockpit that face inward to avoid the possibility of taking direct waves. I’ve seen a few more secure designs over the years but not many. The next time you see a Nordhavn, have a close look and I think you’ll be impressed with the focus on keepting water out while maintaining the excellent high-volume air flow needed for a reliable diesel engine operation. The problem we had is one side of the boat was pushed down the wave below the water line. The good news is that all the mechnical equipment including the engine operated without issue through the event and the bilge pumps got the water out of there in 30 to 60 seconds.

Of the more than 500 Nordhavn’s in service, I only know of a couple that have taken material water ingress through the ER vents. I’ts not that easy to do. Both boats that had this issue, had halfed rolled submerging the vent and were saved by the large ballast deep in the keel favored by Nordhavn that causes the shiny side to pop back up quickly.

Not envisioning this.

Any chance of a quick hand sketch sent to email?

wmdomb@verizon.net

Thanks

bill domb

I’ve sketched it out the system design in words in answer to other questions below and you’ll find more detail at: https://mvdirona.com/2017/12/alarms-at-115am-follow-up/

By the way, have y’all considered installing a few GoPro type cameras around the pilothouse, so that events like this can be visually recorded, rather than only verbally?

Not a bad idea Frank. The problem is we have been boating for 16 years and have only had one event like this. That means we would need to record over 8 million minutes to get the 10 interesting ones :-). Constantly changing batteries and media on the camera wouldn’t be that rewarding. However, setting up a system that is permanently powered and just loops on the media keeping the last N minutes would probably work pretty well. Even more interesting would be to have shots outside. We have seen some pretty interesting and sometimes scary weather but invariably don’t have a picture or video of that. Frequently, I get a shots when things settle down a bit — when things are at the worst, taking a picture or video just never seems like a priority and it would be cool to get some of those shots.

Thanks for sharing experience

Excellent account which highlights the importance of keeping your “cool” when all else around you turns to S.H . one T. With alarms sounding, clear thinking is often lost. I do wonder if your problems on the bar were exacerbated by the “stretch” nature of your particular boat. It would seem to me that had your rudder and propellor been placed, as in the 47, at the stern of your boat, when your rogue wave overtook you, your rudder and propellor would have been in solid water and had significantly more “bite”. The rogue wave lifted your stern and as the propellor and rudder are not stern placed aerated water probably reduced their effectiveness, additionally, your good thinking of maximum power was not directed as effectively as it would have been if the rudder and propellor were close coupled working in non aerated water.

I have read most of your other articles – “Keep up the good work.”

Thanks for the comment Ian. There is no question that few boat operators would ever ask for less rudder authority and certainly I would love to have more on Dirona. A minor correction though in what you have above. The N52 is a stretched 47 but the rudder is moved back 1.5′ over where it is placed on the 47. Arguably, it could have been moved back even more and the further back it is, the more leverage it has on the boat. My thinking is that the closer the rudder has to the stern of the boat, the more power it will have in turning the boat. But I would also think that closer to the stern is more likely to be out of the water during steep wave passage but that’s a guess rather than a fact. The distance between the prop and the rudder would seem important as well.

Some trawlers have made after build modifications to increase rudder power. One common change is to go with an articulating rudder. Multiple rudders is another way to increase wing area.

There is no question you are right that, in these conditions, we all want the most powerful rudder possible. And there is no question that there is some point on all boats regardess of rudder design where a breaking wave of sufficient size will win.

River bars in rough conditions we can avoid. But large breaking waves at sea do happen so I’m very motivated to first work hard to avoid those conditions, then know how to handle the boat to have the best chance of surviving them if we weren’t successful avoiding them. Generally, avoidance is the most effective tactic since even 150′ Alaskan fish boats are lost every year or two.

Recently I was reading of a new recommendation from a Coastal Authority that trains bar crossing crew. Their current training is to apply full reverse gear to stabilise the vessel, when being passed by a breaking wave. Previously I had praised your cool thinking in applying full power and rudder hard over but the logic of applying full power reverse and letting the vessel “weather cock” so to speak would appear to have considerable merit. Presented as food for thought.

Additionally have you given any thought to what effect the towing of a sea drogue might have had.

I understand the logic of using full astern as means to keep a breaking wave from pushing the stern around but I’ll bet that works more effectively in small surf boats with lots of power. It might have been enough to keep Dirona stern to the waves. It’s hard to know for sure. I suspect full astern won’t make much difference with a 110,000lbs getting pushed sideway by a breaking wave coming down from above the boat deck. We have three heavy webbing trailer straps holding the tender on the boat deck and one was broken entirely. The wave force was so high that the cockpit boarding door and the foredeck boarding door both were forced opening breaking their latch assemblies. Waves pack a lot of power.

The logic of full forward is to get water flow on the rudder. The logic of full astern is to “drag” the stern back and prevent broaching. Same approach as a sea droque that you were asking about. I have no expereince with a sea drogue but I suspect it likely would have helped.

One thing I didn’t mention in the original write up that was probably at least a factor is we were running empty fuel tanks. We were planning to calibrate our new fuel tank level sensors in Budaberg which is very close to Big Bay Bar. As a consequence both side tanks were empty and all we have is 15 gallons in the wing day tank and about 50 gallons in the supply tank. Both 835 gallon side tanks were empty. 1670 gallons of diesel is 10% of weight of the boat and way down below the water line. Those tanks carrying some fuel could have helped although I will say the boat popped back up from knock down incredibly fast. However 10,000 lbs of fuel is never a bad thing in rough water. The heavier the boat is the better it feels in rough conditions.

Thanks Steve. There is some fallout remaining from the event remaining. We have some woodwork scratchs from flying furniture but its pretty minor so we’re not complaining.

Thanks for the account and post-mortem! Glad to hear of the happy outcome.

It’s great hearing from the Bella Vita! It’s been too long since those warm nights in the Maquassas. Being in Swains Reefs reminds of the Toumotos Islands from around that same time.

All is well on Dirona. We’re diving and exploring and enjoying the nice weather. We hope you and Brett continue to have a great time on your adventure.

An amazing account of a harrowing experience James! Even we sailers shudder at the thought of that big of a roll. So glad all systems worked as planned and both of you were not hurt. Safe travels! Stacey & Brett, SV Bella Vita

I’m 100% with you Jacques, that big hydraulic bilge pump is a game changer. We just love having it even though in 5 years it’s only been used once outside of normal testing. We also have a small gas powered Honda trash pump that is inexpensive yet very effective. If you flip back through our blog entries in the New Zealand time frame, you’ll find pictures of the last service and test cycle we ran on this pump. It can throw a 2" stream of water about 100′! Another fine piece of gear we hope to never need.

We haven’t heard from you in a while Yair. I hope all is well on your end. Yes, the hydraulic pump is mounted slightly higher on Dirona than the standard bilge pumps. But, I suspect it would actually be even better if it was mounted lower. They hydraulics will operate fine underwater and, the lower the pump, the faster and easier it will prime and start pumping.

You also asked if boat build debris and sea-born matter is a concern with these pumps. It’s a concern with all pumps but less so with the large hydraulic trash pumps. These units are fairly resistent to debris but, yes, debris is always a concern pumping large volumes of water from a boat. None of the pumps had any problem at all in this case but we did have the drain from the forward engine room to main bilge plug up. This drain isn’t needed in that if the level goes above 1′, it’ll flow over the floor pan and into the main bilge. So, that particular drain plugging is not an safety issue.

Frank, I think you are right, the rapidly shallowing water is the dominant factor to creating potentially much larger waves at a bar crossing. Another important contributor is current. If there is outgoing current against the waves, it really causes the waves to stand up.

As always, excellent account on what happened…and how , through preparation, you ended up with a big scare and minor damage>

Another one for the "things to remember" file.

That "silly powerful" hydraulic bilge pump is on my list of "must have" now.

Cheers

Jacques

Excellent post describing a scary scenario with a happy ending. I’m glad you all (and Dirona) are safe. I take it that the hydraulic pumps are mounted higher than the other bilge pumps? Any concern that blockage could affect the hydraulic pumps?

Cheers,

Yair

Glad you and the boat came through that. Is that "river bar" phenomenon similar to the one whereby when arriving in shallow waters, tsunami heights multiply?